Caching, along with naming variables and off-by-one errors, is one of the hardest problems in programming. In this post, we’ll explore caching in a federated GraphQL context from local caching and memoization to distributed caching.

The approaches described here are only one of many ways to cache in a federated GraphQL architecture.

You can find the code describing each strategy here.

No caching: a basic federated architecture

Every good journey has a starting point; ours is a basic architecture with:

- a GraphQL gateway (to consume requests)

- an implementing service (where we define the resolvers)

- and a backend service (to actually retrieve the data for the implementing service)

Since we only have one implementing service at this time, every time a request comes into the gateway, it passes the request to the implementing service to resolve the data from the backend service.

There’s no caching here yet, and you can see an example of this basic no-caching architecture here.

Local caching

Looking at the previous architecture above, you might notice that there’s a one-to-one ratio of requests that come into the gateway and hit the underlying backend service.

If we wanted to reduce strain on the backend service, we could introduce a cache, preventing the need to fetch data that has already been fetched by the implementing service.

A trivial approach is to introduce a local in-memory cache and cache against the API calls that our implementing service makes to the backend service Adjusting the architecture a little bit, our diagram now looks like:

Now, before we call a backend, we check the cache to see if we have made that call recently. If we have, we no longer make that API call and return from the cache. This is our new expected behavior. Our new behavior has reduced our back-end service load by not making the same calls within a short period. For example, if you and I both go to look at the same product on a site, whoever loads the product first will execute a call to the backend service to get that product information, the second one of us will read that data from the cache and not make an API call.

Visit the GitHub repo for this post to find an example of the local caching strategy.

Memoization

When we talk about caching, in most cases, we are talking about memorization. Per definitions.net, memoization is:

an optimization technique used primarily to speed up computer programs by having function calls avoid repeating the calculation of results for previously processed inputs.

Memoization helps us reduce the need to re-run operations that we’ve already performed. If the parameters to a function are exactly the same, then chances are — the output is going to be the same too! This is what our local caching approach is built upon.

For example, if we know that executing `getUser(id:1)` fetches the user with ID = 1, and running it with the exact same parameter will return the same result, we can just save the result, and instead of invoking the request all over again, we can just return the result!

Maybe you can see how useful this is for caching an API call, specifically. The approach to memoizing API calls leads to a lot cleaner code than if we had to cache a variety of search functions.

Here’s the memoization code we could use.

const memoization = (innerFn, getKeyFn, cache) => async (...args) => {

const key = getKeyFn(args);

try {

const cacheVal = await cache.get(key);

if (cacheVal) {

return cacheVal;

}

} catch (e) {

console.log(e);

}

const res = await innerFn(args);

try {

await cache.set(key, res);

} catch (e) {

console.log(e);

}

return res;

};Let’s break down what’s happening above.

We have a function that takes in an `innerFn`, `getKeyFn`, and a `cache`.

The` innerFn` is the function you are trying to memorize and the get key function is used to create a cache key based on the arguments used to execute the function.

The memoization function uses the arguments of the `innerFn` (the function you are memoizing), creates a cache key, checks the cache for a value at that key and returns it if there’s a cache hit (meaning - the item was found).

If there’s a cache miss (the item wasn’t found), it executes the `innerFn`, waits for the result of the `innerFn`, caches that value using the key created by the parameters, and finally, returns the result at the end.

You can find the entire implementation of this function here.

Distributed caching

An in-memory cache works great until you have more than one implementing service in your federated GraphQL architecture.

The in-memory cache loses a lot of its efficiency when this happens, mainly due to the fact that none of the local caches are shared.

But don’t worry; there is a solution to this! A distributed cache helps solve this problem!

Using a distributed cache

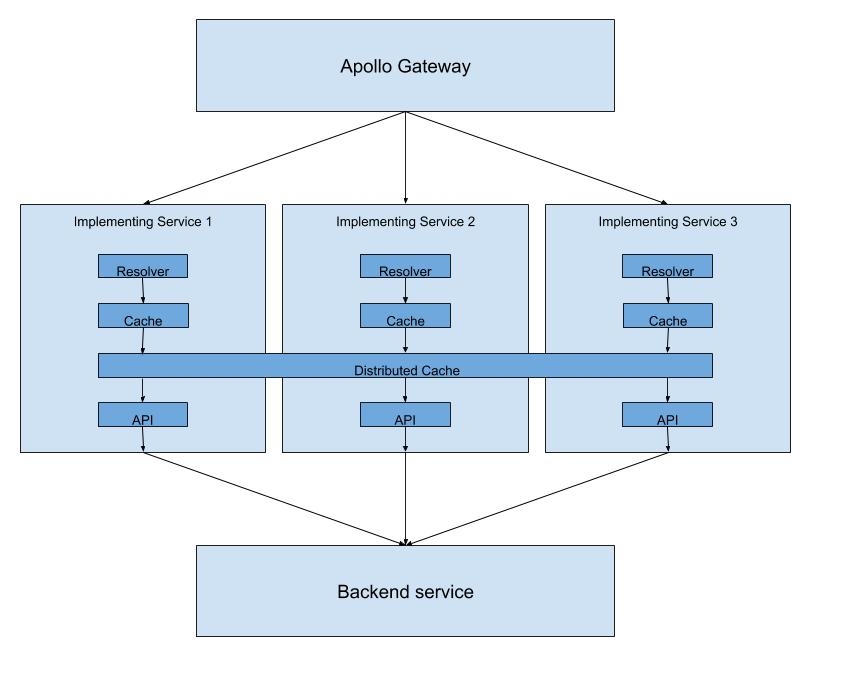

Distributed caches are things like Redis. With distributed caching, your cache can be spanned across multiple implementing servers or services. You can also use NoSQL databases such as DynamoDB and MongoDB as distributed caches. The main idea is that there is a shared object used to save cached values between multiple servers.

If we substitute our existing memoization functions with a cache object that points to a distributed cache instead of a local cache implementation, we get something like this instead:

If you’re using TypeScript, you can strictly type the contract of the cache object that gets passed to your memoization function. You could then switch from using your local in-memory cache to a Redis implementation, a MongoDB one, an Amazon DynamoDB one, etc - whatever you like!

/**

* Generic cache interface that all cache implementations need

* to abide by.

*/

interface ICache {

get (cacheKey: string): Promise<any>;

set (cacheKey: string, value: any): Promise<void>;

}

/**

* Your local in-memory cache

*/

class LocalInMemoryCache implements ICache {

async get (cacheKey: string): Promise<any> {

// implement local in-memory cache function

}

async set (cacheKey: string, value: Promise<any>): Promise<void> {

// implement local in-memory set function

}

}

/**

* Your Redis cache

*/

class RedisCache implements ICache {

private redisConnection: Redis;

constructor (redisConnection: Redis) {

this.redisConnection = redisConnection

}

async get (cacheKey: string): Promise<any> {

// implement redis get function

}

async set (cacheKey: string, value: Promise<any>): Promise<void> {

// implement redis set function

}

}Caching the cache

If you take another look at the architecture diagram, you’ll notice we point a local cache to a distributed cache. We can actually improve performance even further by using two cache objects: one for the in-memory cache, and the other for the distributed cache.

The idea is that by caching locally first, we remove the need to consult the distributed cache on every request - we can start by asking the local one first.

Awe-inspiring benefits to distributed caching

One of the best parts of this approach is how it enables the implementing services in your federated GraphQL architecture to cache things for each other. Let’s expand our architecture a little bit further to include more federated services:

If both implementing services are making calls to the same endpoint in the underlying backend service, they can share that cache value. This is HUGE!

For a practical example, say you have two implementing services: `media` and `product`. Suppose a user searches for a product on your site. That search query ends up calling your `media` implementing service to get the URLs of that product’s pictures.

Using the approach we’ve described, the URLs would get cached in the distributed cache.

When the user then clicks on the product and issues a product query, the request would go to the implementing service for `product`, but thanks to the distributed cache, the URLs for the product’s pictures, which would normally need to have been fetched from the media service, can be pulled directly from the cache!

Further improvement: batching requests

Now that we have some fantastic caching, we can make our system more efficient by introducing dataloader. Dataloader is a marvelous package used to batch requests together (check out the docs to learn more about how it works). We can weave this in right above our API layer but after our caching.

Going back to the product and media example, assume we requested seven products and their images.

If we have three cache hits and four misses, usually, this would mean we make four calls to both the media and products service for the items that we weren’t able to grab from the cache.

Luckily, dataloader comes to the rescue here!

With dataloader right before the API calls, it bundles up all those requests to both the product and media services to fetch the data.

This is a massive deal. Dataloader makes our caching and API fetching logic way less complicated. Due to dataloader caching everything individually, this approach works for any sized group of items.

Conclusion

Well, we made it to the end of our caching journey. We explored caching strategies in a federated GraphQL implementation, starting with zero caching, to two layers of caching and batching with dataloader. We explored the utility of memoization, especially for just getting started caching, and we learned about how it can be composed to improve the way we perform distributed caching as well.

While may be the end of this post, there are millions of other ways to do caching. Two other forms of caching not mentioned in this post are client-side caching and HTTP caching. With client-side caching, you can reduce the amount of data requested via the client, and with HTTP caching using a tool like Varnish, your distributed cache becomes a bubble around a service.

These approaches are amazing, and well worth exploring as you venture other ways to further optimize your GraphQL architecture.